Challenges

Introduction

Humans, unlike the laws of gravity, don’t follow neat equations. Gravity behaves the same way every time; people don’t. After all, we are complex beings running on the most intricate system known to mankind—the human brain.

Science has made enormous progress in understanding the brain’s physiology, mapping out neural circuits and tracking synaptic activity. Yet what remains elusive is the mind itself. That’s where psychology comes in. If neuroscience studies the brain’s structure and signals, psychology studies what those signals become, which is our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. But because these things can’t always be measured directly, psychology often finds itself under fire.

Psychology is a very unsatisfactory science.

Wolfgang Köhler

Critics argue that it isn’t truly scientific, pointing to its reliance on subjective data and its struggle to match the objectivity of the hard sciences. The field’s own replication crisis, where many famous studies failed to reproduce their results, has only deepened that perception.

While these criticisms highlight real methodological challenges, they also risk overlooking what psychology actually studies: the human experience. And human experience, by nature, doesn’t fit neatly into a test tube. It demands tools as flexible as the phenomena it explores.

Take Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) for example. You can’t detect trauma through a brain scan the way you might detect a tumor. While imaging studies have shown that people with PTSD often exhibit heightened activity in regions like the amygdala (which processes fear), these scans aren’t foolproof or meant to diagnose anyone on their own. Everyone’s brain and experiences are different, and it wouldn’t be practical, or ethical, to scan every patient.

A flashback for one person may emerge as physical pain in another, reminding us that distress speaks many languages. That’s why PTSD is mainly diagnosed through behavior and self-report, which makes it seem “subjective.” But just because something is hard to quantify doesn’t make it any less real. It simply reminds us how complex the human mind is, and how good science learns to work with that complexity, not dismiss it.

The same can be said for typology. Typology describes recurring patterns in how people think, feel, and act. These patterns are observable and consistent enough to suggest that something real is happening beneath the surface. Yet, connecting them to the underlying cognitive mechanisms remains difficult with current research tools.

Because of this, some critics would go as far as to call typology a pseudoscience for not being “scientific enough”. But this misses the point. Psychology and typology may deal with abstract and subjective experiences, but they still follow the spirit of scientific inquiry: observing, gathering data, forming theories, testing predictions, and refining conclusions.

Of course, it would be best if the social sciences could achieve the same level of scientific rigor as physics or mathematics. But disciplines that study the human mind often operate in realms too abstract to be measured with the same precision. Science, as it stands, has yet to fully explain human consciousness. And the fact that consciousness remains beyond the grasp of science does not mean it does not exist.

That said, scientific rigor remains crucial. If science takes on too loose a definition, it risks losing its credibility as a source of truth. Still, it is equally important to recognize its limits. There are still many aspects of human experience that science cannot capture. And that’s not a flaw of psychology, but a reflection of how much more there is to discover about ourselves.

Despite these challenges, typology continues to offer meaningful insights into human behavior, giving us a lens to make sense of our differences and similarities in a deeper way.

As science advances, so will we. It is only a matter of time before researchers uncover the deeper mechanics of consciousness. Until then, we will continue refining our frameworks, keeping them aligned with the latest discoveries of the human mind.

Even now, the typology community faces many challenges. By addressing the most common ones, we hope to build a personality system that anyone can use to accelerate their growth.

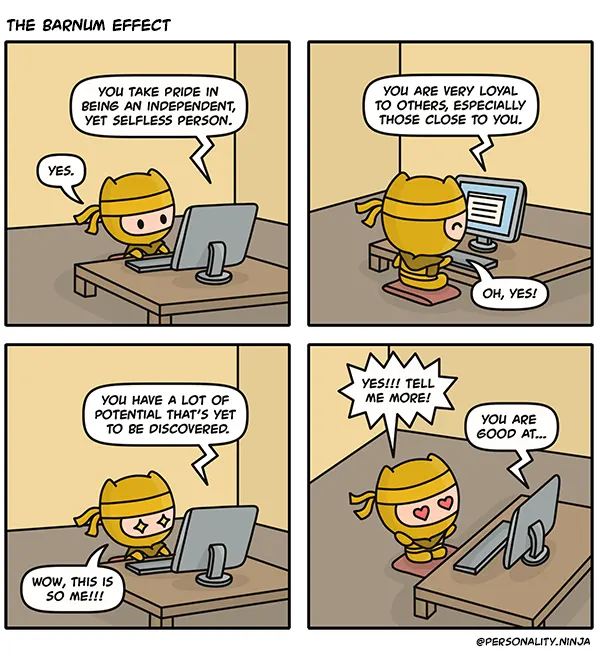

Vague Descriptions

In 1948, American psychologist Bertram Forer conducted an experiment to demonstrate what is now known as the Barnum Effect. He gave his students a personality test but, instead of returning them individualized results, he gave all of them the same exact analysis cut straight from an astrology column in the newspaper.

When asked to rate the accuracy of their test results, the students gave an average score of 4.3 out of 5. It's not surprising that they fell for it. Humans are wired to seek patterns and meaning, even where none exist. We tend to interpret vague or flattering statements through the lens of our personal experiences, making them feel true.

In psychology, this tendency is known as subjective validation, where we validate statements not because they are objectively accurate, but because they resonate emotionally.

And this tendency persists today. Many modern personality frameworks and online quizzes still rely on the same psychological trick. They present users with overly positive and broadly relatable descriptions of their personality, which is why people tend to find their results so convincing even when they’re so general. When we read that we’re “open-minded yet decisive,” or “kind but firm,” we see what we want to see: a balanced, admirable version of ourselves.

The truth is, praise feels good. Compliments trigger small bursts of dopamine in the brain, giving us a subtle reward each time we read something affirming. So it's only natural to be drawn to messages that make us feel valued, special, or exceptional. But left unchecked, these self-affirming messages may do more harm than good, quietly feeding into our ego, inflating our self-esteem and making us resistant to criticism or self-reflection.

On top of that, Barnum statements add little real value. More often than not, the advice they offer is too broad or shallow to target meaningful areas for improvement. They make people feel self-aware without actually becoming self-aware. As a result, they rarely bring about real transformation in people.

Instead of relying on vague statements, personality frameworks should provide type descriptions that are specific and, more importantly, distinct enough for people to see whether the feedback accurately reflects who they are. The clearer the contrasts between traits, the more detailed the picture of a personality type, offering useful insights that actually make a difference.

Equally important, personality frameworks should not shy away from uncomfortable truths to counteract the Barnum Effect. Studies show that people identify more easily with positive statements than with negative ones, for obvious reasons. But real growth can only begin when we confront the inconvenient truths about ourselves.

All in all, a good personality framework doesn’t just tell you what you like to hear, it tells you what you need to hear. Because sometimes, the most valuable insights are the ones that sting a little at first.

Unreliable Definitions

Vague descriptions are tricky enough to work with. But you know what makes things trickier? Undefined terminology.

Imagine you are reading an INFP’s type description. You learn that they are “highly intuitive people who rely heavily on their intuitions to guide them”. Excited, you share your findings on a personality forum, saying that INFPs are imaginative because of their intuition. Someone quickly replies, ”LOL, are you kidding? Intuition is an instinctive understanding of things, NOT imagination.”

So who’s right here? Technically, both of them are. After all, “intuition” was never defined in the first place.

Even simple words can cause confusion when left undefined. A statement like “Perceivers prefer to relax in their free time," sounds straightforward. But the word “relax” can mean many different things. For one person, it might mean staring blankly into the night sky. For another, it could mean planning a detailed trip. See how a single undefined word can change the meaning of an entire sentence?

Sometimes, the issue isn’t missing definitions, but incomplete ones. Take the common claim that Thinkers tend to be more critical of others. At a glance, it sounds reasonable, until you ask: critical in what way? Because Feelers can be just as critical as Thinkers, just about different things. If someone acts against their values—say, cheating the poor—a Feeler can easily unleash a fiery barrage of criticisms, often sharper than a Thinker’s logical dissection.

A more accurate statement, then, would be: “Thinkers tend to be more critical of others when things don’t make logical sense.” The extra layer changes everything.

That’s why definitions matter.

Descriptions help paint an idea, but definitions give that idea shape. Without them, typology becomes a guessing game where everyone projects their own meaning onto the same words. It is the reason why misunderstandings are so common within the typology community. People use the same terms like intuition, feeling, thinking, sensing, but often mean entirely different things.

Unfortunately, many personality frameworks suffer from unreliable definitions. They describe types using loosely defined terms, just like the INFP example above. Ironically, this very ambiguity helps them stay relevant. Ambiguity allows systems to stretch and fit almost any interpretation, making them harder to disprove.

There is no greater impediment to the

advancement of knowledge than

the ambiguity of words.

Thomas Reid

But ambiguity isn’t the only issue that makes typology confusing. Many frameworks also suffer from internal inconsistency—a term researchers use to describe contradictory definitions within a system. This happens when systems put forward two claims that sound plausible on their own, but fall apart when put together.

For example, a system might say that people who advocate for spontaneity are actually structured at heart because they take pride in overcoming their weaknesses. Elsewhere, the same system might also claim that people naturally champion their strengths because it reflects who they are.

So when someone praises the value of being organized, are they expressing a strength or compensating for a weakness? If both are true, then neither can be meaningfully tested.

A strong typology system, therefore, depends on the clarity of its claims. Definitions must be precise and supported by examples of how each concept manifests in real life. It must also be internally consistent. Every rule for determining type should hold true across all cases; otherwise, the framework collapses under its own contradictions.

But above all, a framework must reflect empirical reality. A theory can be internally consistent and logically sound, but if it does not align with how people actually behave, it serves little practical value.

At the end of the day, clarity, consistency, and accuracy form the cornerstone of any objective and reliable personality system. Only by addressing all three can typology evolve into a discipline that is not only conceptually sound but also scientifically valid.

Complicated Jargon

A user manual, no matter how precise, is useless if no one wants to read it. Sure, it may be technically accurate, complete with diagrams and step-by-step instructions, but what good is that if the language is too complicated for most people to understand?

That’s the problem with some personality frameworks today. They are technical and theoretical, relying on complex jargon that only a small circle of typology enthusiasts can make sense of. These frameworks may be highly accurate, but reading them feels like going through a microwave manual—it’s informative, but painfully dry. In trying to be professional and precise, they might end up pushing the average reader away from typology altogether.

Example of a "technical" description:

The attitude of the unconscious as an effective complement to the conscious extraverted attitude has a definitely introverting character. It concentrates the desire on the subjective factor, that is, on all those needs and demands that are stifled or repressed by the conscious attitude.

(Excerpted from Psychological Types, by C. G. Jung, 1974)

On the other hand, we have frameworks that are very scientific and data-driven, but light on explanatory theory. Consider the Big Five. It is widely regarded as the most empirically grounded approach to personality, built from real language data of how people naturally describe each other. Yet, after taking a basic test, you are usually handed a list of percentile scores and… that's it.

You might find out you’re 65% in Conscientiousness, but what does that actually mean? Is it good or bad? Should you try to change it or simply accept it as who you are? More importantly, what does it tell you about your growth, relationships, or goals?

These questions often go unanswered because the Big Five offers little explanation beyond the data itself. You are given cold, hard facts about where you fall along certain personality spectrums, then left to wonder what it all means. For all its scientific rigor, the Big Five offers limited guidance for self-understanding or personal growth.

To put it another way, imagine a geologist who spends years studying minerals. After amassing a wealth of data, he concludes that diamonds are the hardest substance on Earth and ends his research there. People would naturally ask: so what? Apart from being an interesting fact, how does that knowledge help anyone in a practical sense?

Likewise, it is crucial to convert raw data into useful insights in typology. Data is meaningless without theory to give it context and purpose. And theory alone is hollow without data to keep it grounded in reality. A reliable system must offer both: a theory that explains human behavior, and empirical data that supports those explanations in real life.

Yet, even the most well-balanced theories will fail if they are buried under complex terminology. No matter how insightful a model may be, it loses its value if ordinary folks can’t understand it. That’s why, in developing our framework, we focused on making complex ideas like the cognitive processes and energy densities accessible to everyone, all while preserving the depth of its original theory.

After all, the true purpose of any personality framework is not to impress people with how “sophisticated” it sounds, but to empower them through understanding.

At its best, typology should serve as a bridge between understanding and growth—a tool that helps people not only make sense of who they are, but also take meaningful steps toward who they can become.

Other Difficulties

The challenges outlined above describe issues primarily related to the personality frameworks themselves. As mentioned, how a framework is developed and the way it is presented plays a huge role in determining its accessibility and usability.

Therefore, it is clear that building a typology framework is no simple task. Developing the perfect personality system is a delicate process that requires a balance between being too technical and dry, or overly vague and inaccurate.

But the challenges don't stop there. As we will see, the accuracy and effectiveness of typology are not determined solely by the quality of its framework. In the following section, we shall explore a few other challenges that extend beyond the typology system itself.

Read next part → Challenges In Typology II